Things to do on a Sunday

Napier has a number of markets, including one at Clive Square on Saturday mornings–only a 5 minute walk from our door. But we’ve also adopted the habit every other weekend of driving the 20 km to Hastings to visit the Hawke’s Bay Farmer’s Market. It’s a pleasant Sunday drive along the Napier-Hastings highway, and we can always find some good deals on fresh vegetables and fruit.

This week we purchased a huge bunch of silverbeet and a bag of cute looking brussell sprouts (totalling $5.50). We didn’t tarry, however, as we had another reason for ‘travelling south’–we wished to head further down State Highway 2 to the Pekapeka Wetland.

Pekapeka Wetland

The Pekapeka Wetland covers approximately 98 hectares and is situated at the centre of the Poukawa Basin, between the Raukawa and the Kaokaoroa Ranges. Most of the water comes from Lake Poukawa in the south-west, via the Poukawa Stream. The wetland is part of a palustrine swamp (an ancient peat swamp), over nine metres deep in places, and is believed to be one of the oldest swamps in New Zealand, formed around 9600BC.

The surrounding western slopes are capped by Te Aute limestone over calcareous sandstone and siltstone (about 2 million years old). The land on that side has also been contoured by the Wairarapa fault. The last big movement on this fault occurred on 3rd February 1931 at the time of the Napier Earthquake, when the ground shifted 1/2 metre vertically and two metres to the right. The eastern slopes are covered by Te Mata limestone, which is often used as a surface cover for pathways.

The wetland is also bounded by a couple of human-made features; State Highway 2 along the western perimeter, and the Palmerston North-Gisborne railway line on the east.

Wetland facts

- Wetlands contribute to flood control by helping to absorb abnormally high rainfall before it enters our rivers and streams.

- They help manage climate change: healthy peat bogs contain between 2 and 5 tonnes of carbon per hectare, which remains permanently locked in the soil.

- World wetland loss in the last 100 years is estimated to be over 50%. In New Zealand, the loss is estimated to be 90%.

- Many native wetland plants and creatures are threatened with extinction.

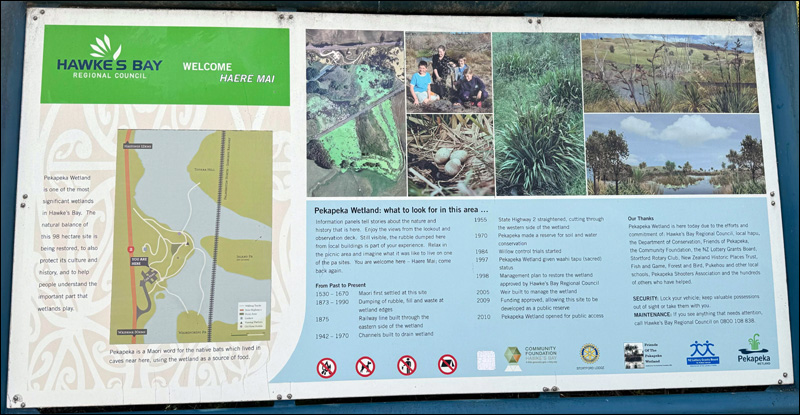

Historical timeline

- 1530-1670: Māori first settled at this site.

- 1873-1990: Rubble, fill and waste were dumped at the edges.

- 1875: A railway line built through the eastern side (Palmerson North-Gisborne Line).

- 1842-1970: Channels were constructed to drain the wetland.

- 1955: State Highway 2 was straightened, cutting through the western side of the wetland.

- 1970: Pekapeka was designated a reserve for soil and water conservation.

- 1984: Willow control trials commenced.

- 1988: Management plans to restore the wetland were approved by Hawke’s Bay Regional Council.

- 2005: A weir was constructed to manage the wetland.

- 2009: Funding to allow the site to be developed as a public reserve was approved.

- 2010: Pekapeka Wetland was opened for public access.

Significance for Māori

Pekapeka means ‘bat’ in Māori, and most likely refers to the bats which lived in the caves nearby, and used the wetland as a food source.

From 1530 to 1670, local Māori used a canoe path through the wetland, from Pakipaki to Lake Poukawa. The area was an important hunting and fishing ground.

Three Pa Sites used the wetland as part of their defences. Waireporepo Pa (just upstream), ‘Island Pa’ (over the railway line). and Tikiwhata Pa, which was a major eel fishing site at the southern end of the wetland, adjacent to Poukawa Stream.

The Pekapeka Wetland has substantial cultural significance for Māori and in 1997, it was granted wāhi tapu status under the Historic Places Act 1993. (Wāhi tapu is defined in the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act (2014) as a place sacred to Māori in the traditional, spiritual, religious, ritual or mythological sense.)

Meandering

It was close to midday and completely calm. The sun was as high as it was ever likely to be in Aotearoa towards the end of August, and it shone at a dazzling angle. Each time I paused to take a photo (which was frequently), I had to look carefully to make sure I didn’t end up in the water.

The boardwalks have been made sturdily, and we followed them as they wove through tall clumps of raupō (Typha orientalis), which at this time of year are a mass of dry, jagged spikes and fuzzy decomposing cattails–although if you looked carefully, the first signs of new growth could be discovered.

It was disappointing, but not unexpected, to read that the wetland had been used as an illegal rubbish dump for all those decades. But I know that it was common for early settlers to consider land to be of no value if it couldn’t be cleared and used for farming. The rubble from a couple of demolished Hastings hotels (the Pacific and the Mayfair) were also dumped in the swamp, and some of the remains have been left on the site for future visitors to chance upon and ponder over. I’ve seen some photos of rubble and wires, but we didn’t come across them ourselves.

There are also places where the pathways travel through patches of regenerative native bush. Here, in particular, the birdsong was very loud. I could hear riroriro, kuihi (flying overhead), pīwakawaka, and tauhou. I could also faintly hear the sound of vehicles racing along State Highway 2.

Birds – doing their thing away from people

What about the birds? (you may ask). Yes, we saw birds from a distance. And we definitely heard them. But the wetland covers a vast area, and the birds can settle a good distance from any humans who might visit. When we first arrived we saw at least three pairs of black swans. They looked as if they had inboard engines–one pair in particular was gliding along the surface at remarkable speed, barely making a ripple. They looked captivating. In a month or two, I’m sure there will be cygnets.

For those who are interested, other bird species that have made the Wetland their home, include kāhu, kawaupaka, kawau tūī, kōtare, the kotoreke, māpunga, matuku-hūrepo (very rare), matuku moana, pīpīwharauroa, poaka, pūweto, ruru, tētē-moroiti, wāna, warou, and weweia.

We’ll definitely visit again. Next time we’ll bring some lunch and see if we can find the hotel rubble. Also, if I’m lucky, I might get some decent photos of the birds.

My blog has relied heavily on information displayed on the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council signage throughout the site.