十九 Overnight Trip to Otaru – Part 3

All good things must come to an end, and so it was with our mini break to Otaru. We’d hoped to be back in Asahikawa by early afternoon, April 04, but had also planned to initially drive back along the coastline so that I could finally walk along a real Japanese beach, and dip my toes in the sea.

Breakfast at Hotel Sonia

We set our alarms for 7.00 am and once we were up and dressed, we met up outside our rooms and headed downstairs for the buffet breakfast. The dining room was moderately busy, with a scattering of Japanese and Chinese travellers, and one other foreign couple–a woman and a man. The former of the two was in the line beside me and was complaining loudly to her companion about the choice of oatmeal. Or apparent lack thereof. Her accent was North American.

Breakfast was arranged buffet style around the edge of the dining room. The food selection was comprehensive, although there weren’t many items that I felt able to eat so early in the morning.

When I looked at my choices, they were unexpectedly colourful, in shades of yellow, orange and pink–a couple of crumbed ebi, a slice of tamagoyaki, a small croissant, a slice of cooked salmon, some diced raw salmon, a dollop of mashed tuna, scrambled egg, and a couple of strips of bacon (just in case you can’t tell from the photo!).

I’d somehow managed to avoid anything green, but I did collect some slices of melon and a few grapes after I’d done my best with the main course. The scrambled eggs were difficult to eat as they were very runny. Usually they’re a safe choice no matter where I’ve been.

Alongside Ishikari Bay

Our plan for the morning was to travel up the coast to Zenibako, about 25 km from Otaru, situated at the bottom of Ishikari Bay. Amiria had previously been there in summer, and told me it was a popular resort area.

On the last stages of our journey to Otaru the previous day, there had been a clear view of the bay and despite the distance I’d noticed a very large and solitary terracotta-coloured building dominating one area of the coastline. I was super curious about what it might be and hoped the mystery would be solved when we headed that way.

Hotel Luna Coast

Zenibako is a coastal settlement with a long stretch of beach, and when we arrived we could not miss the edifice I’d been seeking. It turned out to be the Hotel Luna Coast an ‘adults only’ love hotel (rabu hoteru). It was standing there all by itself, surrounded only by small dwellings. Amiria mentioned that this wasn’t particularly unusual–she said that in Japan there are often tall hotel buildings in coastal areas, but to me it looked completely incongruous. At just on 10.00 a.m., there was no sign of life. Perhaps the hotel was closed for the off season.

There were no car parks in the area, so we had to drive onto the gravelly edge of the road near to a small stream that ran down to the water’s edge. We hoped it would be okay to leave the car there. It wasn’t that we thought that it would be broken into or stolen (this would never happen in Japan), but we didn’t really wish to engage in conversation with a local to explain what we were doing.

Bounty from the sea

On our walk down past the stream, Amiria spotted an Anpanman almost completely buried in the flotsam and jetsam that had accumulated on the bank. The sight was a bit sad–someone’s once-loved toy (possibly?), discarded and forgotten.

It was a blustery grey-gold-blue kind of day, with the dry grasses, the sand, the sea and the sky all displaying versions of the same colour palette. I looked out across the water and realised that directly across from where we were standing (north-west), was Russia, approximately 600 km across the Sea of Japan. Specifically, Primorsky Krai, a ‘federal subject of Russia’, in the Russian Far East. It was hard to get my head around the fact that it was about as close as Auckland would be from Wellington.

It’s disapponting that trash from the Sea of Japan ends up on a stretch of coastline in such an isolated area, and I was depressed by the state of the foreshore. The grey sand was littered with rubbish, from the tiniest of multi-coloured scraps, to plastic bags of all shapes and sizes, to larger plastic drink bottles, to orange and yellow net floats. I didn’t have the heart to take many photos of the human detritus, so have left this to the imagination.

I was, however, interested to read that before the transition to plastic or aluminium, Japanese net floats were fashioned from glass and were predominantly green, due to the use of recycled sake bottles. Clear green globes washed up on the beach would be a far more attractive sight.

Curious, I inspected a few of the larger plastic items and discovered that those that did have any identifiable writing on them, were all Japanese. I’m not sure whether this fact made me feel better or worse. I’d assumed that the trash had washed up from a range of sources, not just from Japan.

We wandered along the water’s edge for about 30 minutes, searching for interesting shells, or seashore flora and fauna to photograph, but were unrewarded. There wasn’t much else to see or do, and with the wind whisking our hair into our faces and finding its way under the cuffs of our jackets and pants, we were getting cold, so we headed back to the car.

I looked back once, to impress upon my memory the overall feel of the place, with the knowledge that it was unlikely that I’d ever stand on that particular shore again. I tried to absorb everything. The feel of the air, the briny smell of the wind, the sharpness of the winter sunlight, the infrequent squawks of the seagulls soaring and diving in the sky overhead.

I’m left with the impression of a vast sweep of barren coastline, curving away in both directions. From the nub of land to the south-east (where Otaru is situated), along and up to the north along Ishikari Bay to Cape Ofuyu. It was April, and in Japanese terms, especially further south, it would clearly be Spring, as that month marks the peak of the Sakura season. Far to the north in Hokkaido, however, it would be another few weeks before the first buds of the cherry blossom began to open.

I decided that although Aotearoa has its own empty swathes of coastline, and although our west coast beaches often have grey or even black sand, the wintry view from Zenibako beach was quite different from one from home. Also the fact that the view from Zenibako beach was dominated by the strange apparition that was the hotel. I couldn’t imagine seeing something similar in New Zealand.

In Hokkaido, once Spring truly starts, everything happens in a really short space of time. I’ve observed this many times in Asahikawa. One minute it’s freezing and the next, it’s too warm. The trees sprout buds and new leaves, the rice paddies turn a brilliant green, new growth pushes through the soil to replace the dry grasses, and wild flowers at the edge of the beaches begin to flourish. The Ishikari Bay coastline was merely in a state of waiting for Summer to arrive.

Back to Asahikawa

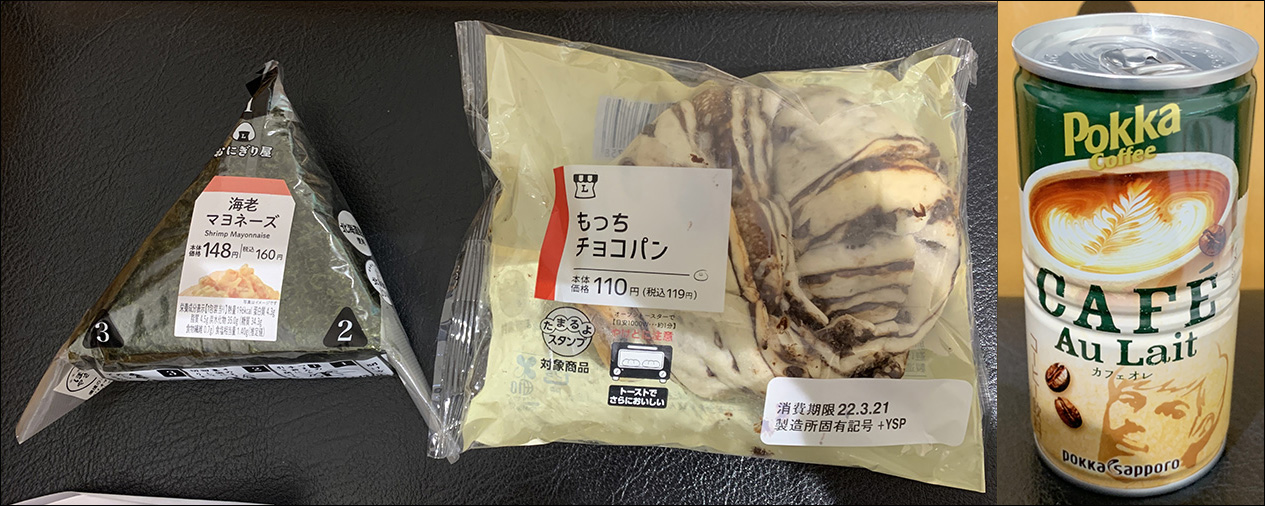

We didn’t waste time on our way back to Asahikawa, only stopping once on the way for a toilet stop, and to pick up some snacks and a drink. At just after midday, I was glad to see the familiar tunnels that indicated we would soon be back in Asahikawa.

On Zenibako Beach

Plastic scraps dispel

memories of green glass spheres.

Grey pebbles rattle.

Jane Percival – 08/08/24

Next Japan Diary: Karaoke in Sangenjaya – a memory from 2023